Overview

I am broadly interested in the intersection of condensed matter physics, quantum information science, and mathematical physics. Some more specific questions I am interested in are:

- What are the effects of locality constraints on

dynamics, eigenstate structure, and the performance of quantum algorithms?

- How can we extend Lieb-Robinson bounds? How can we strengthen them in more restricted cases?

- How can we construct state-transfer protocols that saturate these extended/strengthened bounds?

- What rigorous results can we bring to bear on understanding quantum dynamics?

- How can we extend the adiabatic theorem to understand dynamics outside of that limit, such as those seen in diabatic annealing?

- How can we use tools from functional analysis and operator algebrae to analyze many-body quantum systems?

- How does the algebraic approach to QFT clarify the discussion of quantum phases of matter?

- How can we use quantum computers to better understand physical phenomena?

- What are the underlying complexity-theoretic properties of quantum many-body systems?

- How can we use quantum computers to solve algebraic problems?

This list is by no means exhaustive, nor is it ordered in any particular way.

Previous Work

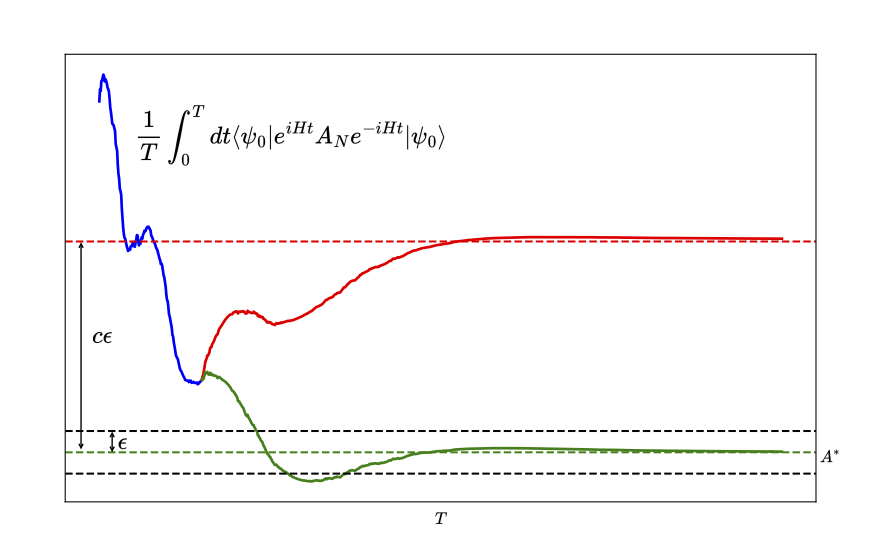

Complexity of Thermalization

One of the fundamental questions of condensed matter physics is understanding how systems thermalize, that is, how their dynamics transition from being influenced by their initial conditions to that described by equilibrium statistical mechanics. This is well understood in the classical setting, but for closed quantum systems, there is still quite a bit of fundamental work to be done. Our work analyzes the thermalization of open quantum systems from the perspective of computational complexity theory. We build off a recent result proving the undecidability of thermalization in the thermodynamic limit, showing PSPACE completeness of the lab-relevant setting of systems with finite size. See our paper here.

One of the fundamental questions of condensed matter physics is understanding how systems thermalize, that is, how their dynamics transition from being influenced by their initial conditions to that described by equilibrium statistical mechanics. This is well understood in the classical setting, but for closed quantum systems, there is still quite a bit of fundamental work to be done. Our work analyzes the thermalization of open quantum systems from the perspective of computational complexity theory. We build off a recent result proving the undecidability of thermalization in the thermodynamic limit, showing PSPACE completeness of the lab-relevant setting of systems with finite size. See our paper here.

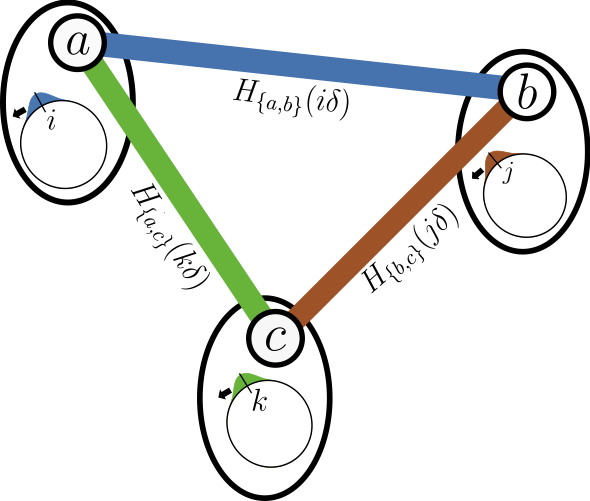

Time-Independent Lieb Robinson

Lieb Robinson bounds serve as emergent limitations on the speed of information propagation in non-relativistic quantum many-body systems, and are indispensable tools for proving many results in mathematical physics. To establish tightness of the bounds, we can construct protocols that propagate information in a way that saturates them. The proof of the Lieb-Robinson bound makes no assumptions on the time-dependence of the system, and many of the protocols used to show tightness are highly time-dependent. This leads to a natural question: can we saturate these Lieb-Robinson bounds with time-independent protocols, or are the Lieb-Robinson bounds for time-independent systems asymptotically tighter?

Lieb Robinson bounds serve as emergent limitations on the speed of information propagation in non-relativistic quantum many-body systems, and are indispensable tools for proving many results in mathematical physics. To establish tightness of the bounds, we can construct protocols that propagate information in a way that saturates them. The proof of the Lieb-Robinson bound makes no assumptions on the time-dependence of the system, and many of the protocols used to show tightness are highly time-dependent. This leads to a natural question: can we saturate these Lieb-Robinson bounds with time-independent protocols, or are the Lieb-Robinson bounds for time-independent systems asymptotically tighter?

In two papers, we begin to answer this question, giving evidence that time-independent systems propagate information as quickly as their time-dependent counterparts. In the first paper, we engineer state transfer protocols that saturate the Lieb-Robinson bounds for free-particle systems with power-law decaying coefficients. In the second, we use a modified clock construction to make pre-existing optimal time-dependent protocols time-independent, at a cost of a super-extensively growing (logarithmic in system size per qubit) number of ancillary qubits. Both of these settings are able to saturate the Lieb-Robinson bound with time-independent protocols, suggesting that we should be able to do so as well in the general case. See our two papers here and here.

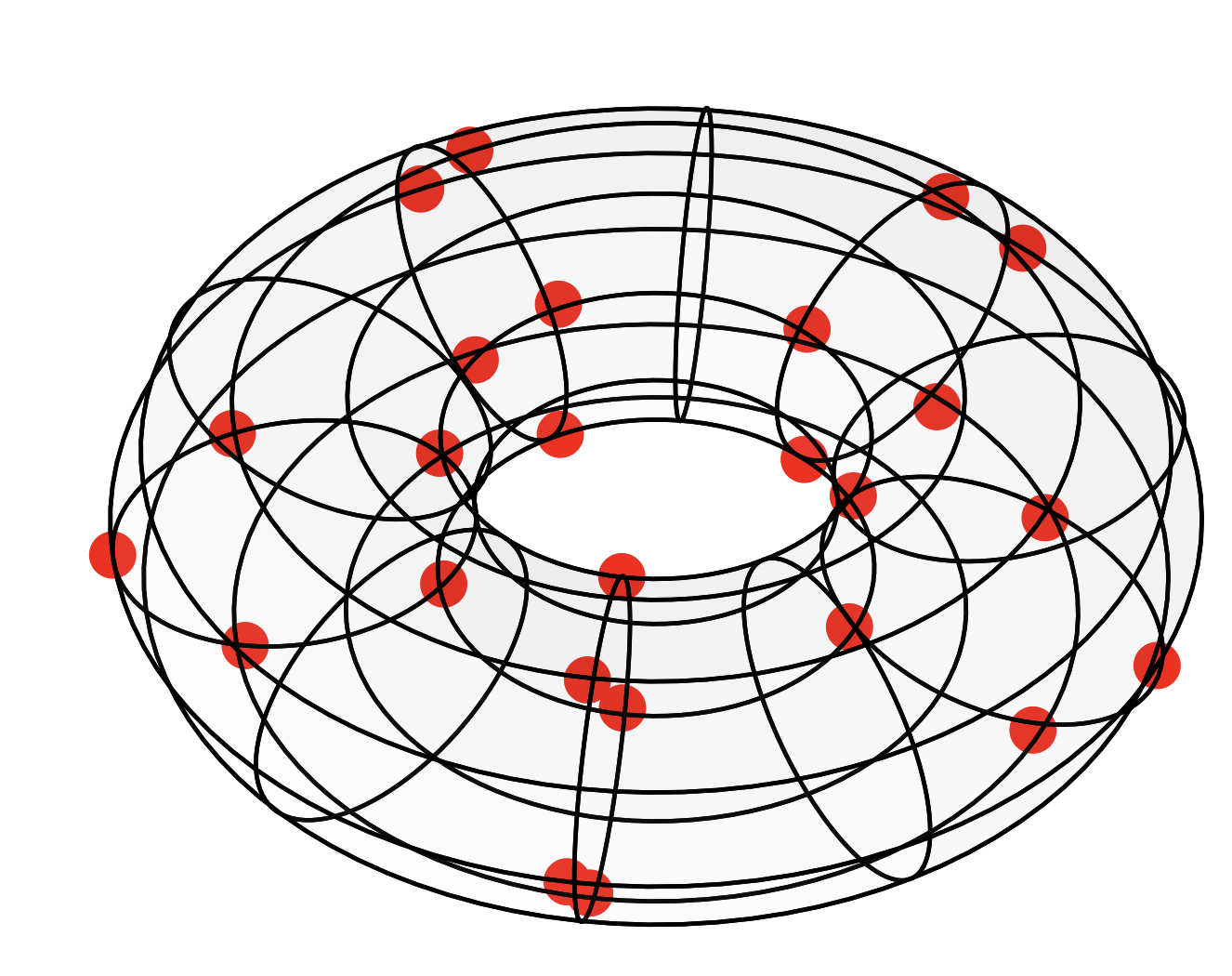

Projective Toric Designs

Designs are sets of points in a probability space which capture the behaviour of the total space up to some level of complexity; more explicitly, averaging a sufficiently simple function over the points of a design equals the function’s average over the whole probability space. Designs are of interest to the QIS community for their applicability to a wide variety of subfields, such as quantum sensing, tomography, cryptography, and error correction. In this work, we investigated a new type of design, a toric design, which is in some sense a design on the phase information of the space of quantum states. They can be combined with designs on the unit simplex (the amplitude information) to construct quantum state designs. We found that the problem of constructing minimal toric designs was related to open questions in the field of additive number theory, specifically regarding notoriously unstructured objects called Sidon sets, as well as the study of mutually unbiased bases. See our paper here.

Designs are sets of points in a probability space which capture the behaviour of the total space up to some level of complexity; more explicitly, averaging a sufficiently simple function over the points of a design equals the function’s average over the whole probability space. Designs are of interest to the QIS community for their applicability to a wide variety of subfields, such as quantum sensing, tomography, cryptography, and error correction. In this work, we investigated a new type of design, a toric design, which is in some sense a design on the phase information of the space of quantum states. They can be combined with designs on the unit simplex (the amplitude information) to construct quantum state designs. We found that the problem of constructing minimal toric designs was related to open questions in the field of additive number theory, specifically regarding notoriously unstructured objects called Sidon sets, as well as the study of mutually unbiased bases. See our paper here.

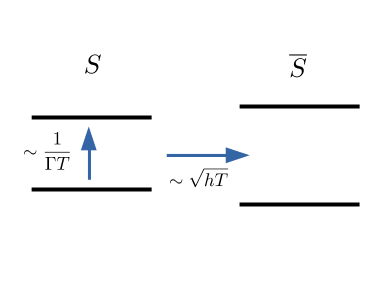

At slow-enough timescales, quantum dynamics starting in the ground state are rigorously governed by the adiabatic theorem, which guarantees approximate spectral transport, with error (heuristically) scaling like \(\sim(\Gamma^2 T)^{-1}\) where \(\Gamma\) is the spectral gap of the Hamiltonian. These guarantees have been harnessed, for instance, to give an alternative method of quantum computing equivalent in computational power to the standard one; to perform a computation, one need only evolve a given input state by a family of Hamiltonians whose initial ground state is the input state and whose final ground state is the output.

At slow-enough timescales, quantum dynamics starting in the ground state are rigorously governed by the adiabatic theorem, which guarantees approximate spectral transport, with error (heuristically) scaling like \(\sim(\Gamma^2 T)^{-1}\) where \(\Gamma\) is the spectral gap of the Hamiltonian. These guarantees have been harnessed, for instance, to give an alternative method of quantum computing equivalent in computational power to the standard one; to perform a computation, one need only evolve a given input state by a family of Hamiltonians whose initial ground state is the input state and whose final ground state is the output.

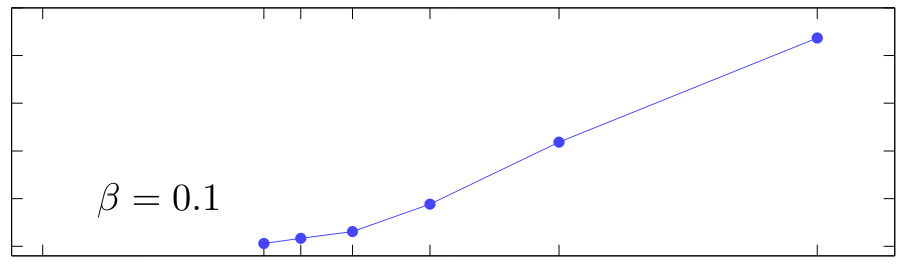

However, while the adiabatic theorem serves as a rigorous bound, in some cases, it is only that, a bound. For some systems one can arrive at the final ground state much quicker than would be suggested by the adiabatic theorem’s error scaling. However, these examples have mainly been studied only heuristically and numerically. In this work, we used techniques from spectral graph theory and matrix analysis to more rigorously understand the error behaviour in these sub-adiabatic regions. See our paper here.

Lefschetz Thimble Monte Carlo for Spin Systems

A widely used class of classical algorithms for simulating quantum many body sytems is quantum Monte Carlo (QMC). QMC works remarkably well for some quantum systems, but when a system has what is called a sign problems, where the quasiprobabilities it samples oscillate to rapidly in phase, it struggles, having the run-time required to keep constant relative error scaling exponentially with inverse temperature and particle number. It is known that the sign problem is NP-hard, but nevertheless heuristic mitigation strategies can be applied to specific systems, sometimes to remarkable effect. One such mitigation strategy is called Lefschetz Thimble Monte Carlo (LTMC), which maps the original integration manifold onto combinations of stationary phase manifolds, each of which have no sign problem, and samples from them. This method is designed to work for state spaces with continuous bases, such as position, but they don’t readily apply to discrete ones, such as spin. In this work, we applied LTMC to spin systems and tested it on some basic spin systems as a proof-of concept. Along the way, we also found numeric verification for the fact that the standard spin-coherent state path integral’s continuum limit does not correspond to the partition function in many basic cases. See our paper here.

A widely used class of classical algorithms for simulating quantum many body sytems is quantum Monte Carlo (QMC). QMC works remarkably well for some quantum systems, but when a system has what is called a sign problems, where the quasiprobabilities it samples oscillate to rapidly in phase, it struggles, having the run-time required to keep constant relative error scaling exponentially with inverse temperature and particle number. It is known that the sign problem is NP-hard, but nevertheless heuristic mitigation strategies can be applied to specific systems, sometimes to remarkable effect. One such mitigation strategy is called Lefschetz Thimble Monte Carlo (LTMC), which maps the original integration manifold onto combinations of stationary phase manifolds, each of which have no sign problem, and samples from them. This method is designed to work for state spaces with continuous bases, such as position, but they don’t readily apply to discrete ones, such as spin. In this work, we applied LTMC to spin systems and tested it on some basic spin systems as a proof-of concept. Along the way, we also found numeric verification for the fact that the standard spin-coherent state path integral’s continuum limit does not correspond to the partition function in many basic cases. See our paper here.